If a neighborhood, by definition, is "a district or locality, often with reference to its character or inhabitants," Farid Matuk's This Isa Nice Neighborhood from Letter Machine Editions explores the ramifications of a increasingly global culture and economy on the neighborhood-concept through the aesthetic lens of a poetry. A poem such as "Hollywood," for instance, presents the reader with a personal, thus local, scene in its incipient lines: "Why shouldn't I take your pills / you've got the hospice Percocet all day" (69). If we assume, based upon the poem's title, that we can locate the speaker in Los Angeles, an abrupt alternation in geography occurs just one line later: "normally that lane in Kabul would be thick / with schoolgirls / but the Taliban came through." Moments later, the speaker states: "I'd like to go piss outside / to affirm life Dallas is / everywhere"; then, once again, the poem returns to Afghanistan, but via a British television broadcast: "President Karzai is not afraid, BBC says." Such dislocations occur throughout the poem, as well as throughout the collection as a whole, but these dislocations, or "parts of the poem / levitate at once / into a constellation" (73) so as to develop a loose but highly constructed relationship with one another.

Toward the poem's closing, the speaker informs us that "we said Hollywood without end / until it meant nothing and your home / was in your voice." To wit, the speaker suggests that the proliferation of naming (or viewing or clicking-through that matter) in our contemporary culture has evacuated the particularized "character" out of our localized neighborhoods; while this, no doubt seems a bit fatalistic, hope resides in the articulation of the now absent as it re-locates within "your voice." Of course, this is by no means a resolution, as we've already been told throughout the collection of the dangers or mis-communications inherent to that "voice." Take, for instance, the first stanza of the poem "Of Our Porvenir (future, fortune)":

Montezuma meets Cortés

Pizarro greets Atahualpa

each says I can't imagine

what will come their interpreters

say neither can we (37)

The "interpreters," unable to translate these disparate voices, do not know "what will come" with regard to language, and neither do the indigenous leaders nor their European counterparts know "what will come" with regard to their cultural narratives. But, we as contemporary readers do know "what will come"; and, at least for the Incas and the Aztecs, it is a sad tale of genocide. This certainly does not mean that localized/particularized narratives disappear, or that European-based narratives will maintain a rigid and eternal hegemonic stranglehold upon historical and cultural development, but the passage does signal, or allude to certain power struggles expressed through/in "voice" and language that occurred, occur, and will occur when neighborhoods interact, conflate, and re-organize. Or, as the in media res poem "All Stories Great and Small" begins:

are over. are being allowed to merge

by a friendly motorist. are on their way.

are having their wrists turned

toward the sun, someone having demanded, show yourself.

are loving your high, Elizabethan brow

so much they say, blah, blah, blah. (5)

In these opening lines, then, the speaker tells us that narrative (i.e. "All Stories") "are over," but also that they "merge" into some busy thoroughfare of a general history or modern narrative, perhaps. Likewise, something orbital (transcendent?) demands that a narrative "show yourself," in some hope, maybe, of transparency as to their construction; or, just as likely, a modern narrative, such as US Weekly or TMZ, may only be concerned with entertainment and its corresponding aesthetic features (i.e. a "high, Elizabethan brow") that comes to and through us as nothing more than "blah, blah, blah."

Of course, poems that convey the political or social oftentimes read as didactic or heavy-hand, but Matuk guards against this by implicating the speaker of his poems, thus communing with his readers, as well as those others he implicates. In the closing piece "Tallying Song," the speaker declares:

I am 34

my bank account

keeps growing slow

the dog is safe, healthy

we have jobs

nothing to stop us (125)

Regardless of contemporary society's ills, or the ills of previous societies that enabled us to arrive at where we are today, the speaker (whether sarcastically or sincerely) acknowledges an ease within his rather bourgeois life-style, one that predicates itself upon uneven binaries and power dynamics so as to maintain an existence that allows for the following:

It's Saturday

the sun looks warmer than it is

I've rolled down my pinstripe oxford

to full sleeves

slipped into my cardigan

a macaroon in

my mouth

flowers in our neighbors' yard

about their plaster fountain

I dress in the styles

of the rich

feel safe (126)

In the end, I would argue that the strength of This Isa Nice Neighborhood is that it does not cater to a final resolution or look for a way to tidy-up the complex relationships, whether economic, cultural, sexual, or national, that we encounter in today's world. Instead, we are left, mostly, with questions for how we can best navigate these new boundaries of the global-neighborhood wherein we now find ourselves. To this extent, Matuk's speaker asks near the close of the collection: "By what means and bodies do we make extensions, change ourselves, I mean in the real world, which is the one we make?" (128) In the question, perhaps, lies the answer.

Toward the poem's closing, the speaker informs us that "we said Hollywood without end / until it meant nothing and your home / was in your voice." To wit, the speaker suggests that the proliferation of naming (or viewing or clicking-through that matter) in our contemporary culture has evacuated the particularized "character" out of our localized neighborhoods; while this, no doubt seems a bit fatalistic, hope resides in the articulation of the now absent as it re-locates within "your voice." Of course, this is by no means a resolution, as we've already been told throughout the collection of the dangers or mis-communications inherent to that "voice." Take, for instance, the first stanza of the poem "Of Our Porvenir (future, fortune)":

Montezuma meets Cortés

Pizarro greets Atahualpa

each says I can't imagine

what will come their interpreters

say neither can we (37)

The "interpreters," unable to translate these disparate voices, do not know "what will come" with regard to language, and neither do the indigenous leaders nor their European counterparts know "what will come" with regard to their cultural narratives. But, we as contemporary readers do know "what will come"; and, at least for the Incas and the Aztecs, it is a sad tale of genocide. This certainly does not mean that localized/particularized narratives disappear, or that European-based narratives will maintain a rigid and eternal hegemonic stranglehold upon historical and cultural development, but the passage does signal, or allude to certain power struggles expressed through/in "voice" and language that occurred, occur, and will occur when neighborhoods interact, conflate, and re-organize. Or, as the in media res poem "All Stories Great and Small" begins:

are over. are being allowed to merge

by a friendly motorist. are on their way.

are having their wrists turned

toward the sun, someone having demanded, show yourself.

are loving your high, Elizabethan brow

so much they say, blah, blah, blah. (5)

In these opening lines, then, the speaker tells us that narrative (i.e. "All Stories") "are over," but also that they "merge" into some busy thoroughfare of a general history or modern narrative, perhaps. Likewise, something orbital (transcendent?) demands that a narrative "show yourself," in some hope, maybe, of transparency as to their construction; or, just as likely, a modern narrative, such as US Weekly or TMZ, may only be concerned with entertainment and its corresponding aesthetic features (i.e. a "high, Elizabethan brow") that comes to and through us as nothing more than "blah, blah, blah."

Of course, poems that convey the political or social oftentimes read as didactic or heavy-hand, but Matuk guards against this by implicating the speaker of his poems, thus communing with his readers, as well as those others he implicates. In the closing piece "Tallying Song," the speaker declares:

I am 34

my bank account

keeps growing slow

the dog is safe, healthy

we have jobs

nothing to stop us (125)

Regardless of contemporary society's ills, or the ills of previous societies that enabled us to arrive at where we are today, the speaker (whether sarcastically or sincerely) acknowledges an ease within his rather bourgeois life-style, one that predicates itself upon uneven binaries and power dynamics so as to maintain an existence that allows for the following:

It's Saturday

the sun looks warmer than it is

I've rolled down my pinstripe oxford

to full sleeves

slipped into my cardigan

a macaroon in

my mouth

flowers in our neighbors' yard

about their plaster fountain

I dress in the styles

of the rich

feel safe (126)

In the end, I would argue that the strength of This Isa Nice Neighborhood is that it does not cater to a final resolution or look for a way to tidy-up the complex relationships, whether economic, cultural, sexual, or national, that we encounter in today's world. Instead, we are left, mostly, with questions for how we can best navigate these new boundaries of the global-neighborhood wherein we now find ourselves. To this extent, Matuk's speaker asks near the close of the collection: "By what means and bodies do we make extensions, change ourselves, I mean in the real world, which is the one we make?" (128) In the question, perhaps, lies the answer.

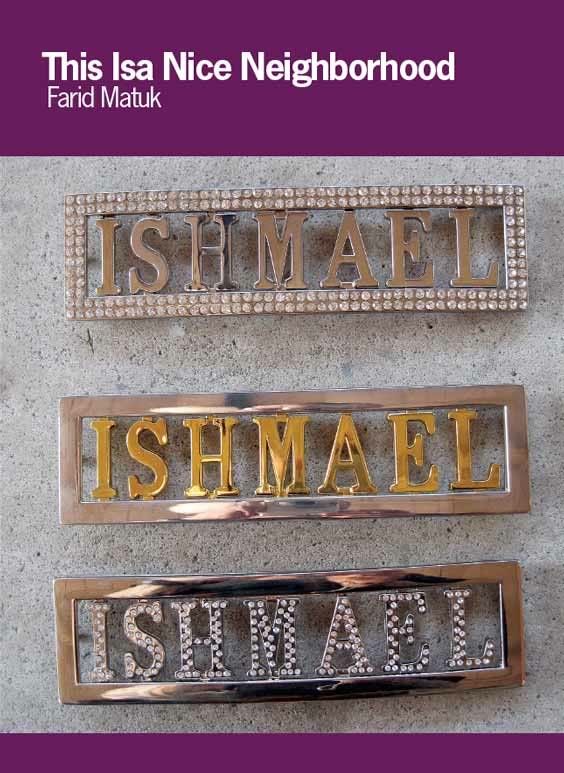

Well said, well said--you failed to mention, however, how nice the actual artifact itself is.

ReplyDelete